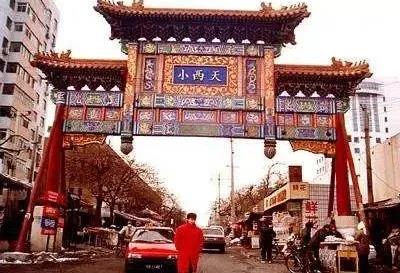

Before 2016, Xiaoxitian in April was not only a hot spot for movies but also for street barbecues. If I got up very early, queued and managed to buy a ticket for a late night movie, I became the happiest man in Beijing. Because I knew by the time I got out of the big screening hall of the China Film Archive Art Cinema at the end of the movie, there would be street barbecues by the curb welcoming us passionate film fans.

Back then, April was not just about watching the best films from around the world in Beijing, but more about enjoying the most artistic street barbecues in Xiaoxitian.

In the evenings during the Beijing International Film Festival (BJIFF), against the dim street light of the Wenhuiyuan Road and barbecue smoke, there were five to six distinct young men and women sitting at each table, debating something in small voice. It looked very much like a scene from A City of Sadness. However, they were discussing Orson Welles, King Hu and Andrei Tarkovsky.

While serving dishes, an owner of the street barbecues would sometimes jump in their endless debate with his views. I had nothing but the highest respect for all the owners of the street barbecues when I heard one of them closed his business for one night to watch the sold out Once Upon a Time in America.

No, not just owners of street barbecues. The spell of films was casted on the whole city. Even those old ladies and gentlemen walking dogs on the street became unfathomable because of the BJIFF.

Maybe, that’s the magical power of the BJIFF.

If every film festival had a name for their magic, then the magic of the BJIFF might be a touch of humanity hidden in the human world. It may sound ordinary but when the whole city were on the go because of the BJIFF, especially in the extraordinary times like this year, the magical power of the film festival and screened films made it.

In the blink of an eye, the BJIFF marked its 10th anniversary. This year’s edition was special, not because of the disappearance of smoky street barbecues, but the unexpected pause of the whole world, including the canceled Festival de Cannes in 2020 and postponed Venice International Film Festival. In this sense, the 10th BJIFF naturally became extraordinary as compared to previous editions.

Nevertheless, Beijing nailed it in the toughest moment.

After a long pause of the film industry due to the pandemic, the postponed BJIFF held in August meant so much: reopening of film festivals, and more importantly, a big hope to boost the film industry and confidence in the film market. The “Film Marketing and Distribution Loan” announced at the Summit on China’s Film Investment and Financing aimed to get more filmmakers through the tough time.

Number 10 was supposed to signify successful conclusion of one cycle and brand new beginning of another. It was totally unexpected how the 10th BJIFF would be faced with such a huge challenge against its influence.

Fortunately, the BJIFF’s magical power became even stronger as time went by. It enabled candid exchanges among the audience and creators. It was more open to arthouse films and invested more creativity into the genre. In terms of the market, it worked hard to find a way upward.

As we suffered from the pandemic, the film industry needed restarting. At this time, the BJIFF not only commemorated the previous editions over the past decade, but also stood at the cusp of the reopening of the industry and opened a chapter of review and reboot of the China’s film industry.

For the 10th edition, the BJIFF strove for the best, and presented unprecedentedly new ecology of film festivals that integrates technologies, advocacy for art and market orientation. With diverse horizontals and dimensions, this edition represented China film well.

We experienced parting with films from January to July, wait for the BJIFF from April to August and finally had the reunion in August. The temporary parting with films rendered more well-mannered, eager and picky audience. Despite the changed environment, the audience remained passionate. In 10 minutes, 72% of offline screening tickets were sold out. Such a moving explosion of passion for going to movies after long-term repression was set off both offline and online.

The 10th edition was all about online celebration. I first planned to wait and see how it went. But I was absolutely impressed that several meet-and-greet with cast & crew was as good as on-site editions.

After one year at the same venue—grand screening hall of the China Film Archive, The Reunions directly by Da Peng managed to integrate the short film The Final Reunion and Ruyi.

The Reunions is so unique. One year ago, the first half of the work The Final Reunion held a meet-and-greet with cast & crew at the China Film Archive. A year later, the complete work was screened at the China Film Archive again. And those that participated in the first half’s meet-and-greet were amazed to find out they became part of the complete work. The boundary of watching and being watched is broken. Those staring at the screen were started back by the screen.

Besides, The Reunions was the only Chinese film selected into the Outlook Section. In the vortex of fictional and factual presentation, the boundary between fiction and facts was broken, and layers of intertextual narration were used in the reconstructed work.

At the meet-and-greet session, Sha Dan thought the film was fascinating. To certain extent, such fascinating effect would not be possible without the combination of the avant-garde setup of screening sections of the BJIFF and the experimental work.

From Encounters of the Berlin International Film Festival to the Outlook of the BJIFF, excellent film festival curators aimed to bring brand new experience to the audience via technologies or creative ideas.

Da Peng met and greeted the audience online, “That was how the work was planned in the beginning. One crew shot The Final Reunion, while the other crew shot how I shot The Final Reunion, which became the Ruyi.”

Different from other online meet-and-greet activities, the cast and crew were unloading their thoughts. All the questions and answers were carried out in a candid and relaxing manner. Da Peng talked about creative ideas, creation, incidents in shooting, and how he took the opportunity to solve the incidents. He almost had the uttermost revelation of how the film was produced. Such completely frank exchanges were rare under most circumstances, let alone the online chatting.

In the context of the BJIFF, both creators and the audience opened their heart, and exchanged their thoughts about films back and forth just like neighbors, colleagues, classmates and friends.

A decade-long commitment to films. The 10th BJIFF held the masterclasses and workshop for the first time, and managed to integrate dreams, pathways and trends of films.

Ang Lee, Stanley Kwan, Jessica Hausner and renowned Hollywood producer Andre Morgan walked the audience through the original aspiration and future of the film.

I found Ang Lee Masterclass is the most intriguing out of the four. He was presenting oriental expression of films and digital technologies when he was disconnected because of technical glitches, in which way the necessity of upgrading digital technology was proven on the site.

Lee was candid and modest as in front of young filmmakers and the audience. He tried to give very detailed explanation for every question, and unloaded his worries about future.

“I am as confused as you are. The cinema is having a tough time. And it’s difficult to get back to where we used to be. It’s hard for a crew of hundreds of personnel to shoot a film at anyplace now. Everyone is getting used to watching films at home. Thus, it’s hard to predict how the cinema would become. Maybe those high-end cinemas or those equipped with special experience might survive. Not the same with other cinemas. People are able to and getting used to watching films on TV and their phones. Hence, we have to figure out new ways of filming works, and start a revolutionary reform.”

It’s secretly delightful to know that even masters would get confused. However, they would not stop at being confused. Lee’s seeking new technologies and changes on his way forward, and he’d like to add new perspectives in the audience’s viewing experience via content expressions and technological support.

The way forward is right in front of you. And the MPA Representative Workshop presented more practical approaches.

Due to the impacts of the global pandemic, this edition of the MPA Representative Workshop somehow signified that we were all in this together. It discussed how we can develop a highly industrialized system that assures good production and prevents risks, and sought for more cooperation and possibilities.

As a matter of fact, with or without the pandemic, the BJIFF is always a cooperative youth who’d love to make friends from around the globe, and keep curious and keenly abreast of the trends of global films.

The Little Joe directed by Jessica Hausner kept drawing attention from the Festival de Cannes to her masterclass held in Beijing. It’s beyond doubt that the combination of feminine perspective and sci-fi is a major trend of global films this year. The well-paced masterclass presented to Beijing the presence of female filmmakers in the international community.

In addition to newly added masterclasses and workshop, there were the Industry Conversations and Project Pitches led by young filmmakers.

Masters and rising stars, classics and innovation. The BJIFF’s blending of senior and junior generations filled in the gaps between generations, and enabled the industry to see its future and pinnacle.

Industry Conversations by young filmmakers

This edition of the BJIFF was nicer and friendlier with arthouse films and related creators. Moreover, it prepared pleasant surprise for them.

In this year’s film list, arthouse films and related creators were highly acclaimed in screenings and forums. Arthouse film fans sure had much more access to their passion, such as The Work and Days, an almost 10-hour long film recording daily life.

The Work and Days

It was daring to screen a 520-minute long film, which proved BJIFF’s confidence in selecting and screening arthouse films.

To be more exact, it’s more of bilateral confidence. The Work and Days was awarded the Best Film in the Encounters section of the Berlin International Film Festival. The honor somehow assured the artistic value of the film, and boosted the confidence of the curators in selecting the film. But more than that, trust in the audience mattered as well.

The BJIFF needs serving the audience, the latter in turn is served, understood, guided and enhanced. The 450-minute long Sátántangó screened in the last edition of the Shanghai International Film Festival, China nailed a self-exam. This year, the BJIFF tested its decade-long commitment of fostering the audience’s interest in arthouse films with the 520-minute film.

The Work and Days

300 tickets priced at 320 yuan/ticket were snapped up upon launch. As a fan who failed to book a ticket, I sincerely advise the BJIFF to remain daring and screen more similar films.

The ticket booking was really challenging. Every April (August in this year’s edition), you would see ticket grabbing ads on all the social media. The interactive Late Shift with full immersion was definitely one of the movies to which tickets were the hardest to get.

How should I describe it? It was unprecedentedly unique. Throughout the viewing process, I was busying watching the movie while reading plots on my phone. It was absolutely once-in-a-lifetime experience where all the audience was justified in checking their phones for multiple times.

Late Shift

The film festival enables us to watch classics, expand our viewing experience via films such as the Late Shift, and enjoy works that break the boundaries such as the “5x1” VR film. The underlying charisma of films is about jumping out of the box. By keeping this in mind, the festival keeps the original aspiration of films.

Those cutting-edge films will update viewing experience of the audience and push the frontier of the screening sections of the BJIFF.

Virtual Reality Section

When more films in the same genre are released, there will be more room for creators of such arthouse films.

The 10th edition solved difficulties in booking tickets to certain extent. Even if you failed to book a ticket to offline screening events, you may spend 12 yuan on iQIYI in streaming the Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains directed by Gu Xiaogang, and appreciating the Fuchun river instead of going to the cinema.

The online BJIFF launched this year meant so much more than films online. It managed to merge the festival’s online and offline events and activities, and its all-round in-depth cooperation with iQIYI fully broke the deadlock between foreign streaming media and international film festivals.

From this perspective, the BJIFF is open to new concepts, and pioneering in forging ahead, surpassing itself and pushing the frontiers of films.

Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains

If we are to make divergent thinking on the online BJIFF, you’ll notice that the 10th edition has defined a new start line for its next decade.

Along the start line there are new ecological features distinct from other international film festivals—good interaction with streaming media and the Internet, as well as multi-way and multi-dimension interaction among filmmakers, audience, market and the film industry.

Such interaction is just like films with its unique temporal dimension. Let’s join the city while enjoying a film carnival in a new way.

You may watch a movie, sitting upright; enjoy a movie online or outdoors together with family members and friends; and keep immersed in and interactive with films by getting rid of media restriction.

This might be the right way for the BJIFF to stand out among global film festivals.